Street Epistemology - Changing One's Mind

The term 'Street Epistemology' (SE) appeared in the provocatively titled book A Manual For Creating Atheists around 2013. It's important to note that it was not the author, philosopher Peter Boghossian, who apparently chose the title but his publisher. 'Street Epistemology' just isn't a catchy title. But if you want a book to be read in the USA, the most hyper-religious of all the wealthy countries of the world, arguing a redefinition of 'faith' as 'pretending to know things you don't know' will tend to attract attention.

I'll mention it now (and have to repeat it often) that although SE is often used when discussing religious belief, faith itself is not an exclusively supernatural belief, it is just a type of epistemology or method of reasoning that can lead to the building of unreliable knowledge or in fact no real knowledge at all. Faith is essentially having a guess and never revising it. It is to apply a seal to the possibility of any significant amendment or alteration including dismissal or un-belief. It argues against something as simple as changing one's mind. That's what epistemology is, the 'study of knowledge' or how we go about establishing what we claim to reliably know. And that process has to include by definition the possible revision of any belief, otherwise one is not engaging in the process of building knowledge. They are merely defending belief. Faith thinking is confirmation bias in one never ending loop. Boghossian pointed out that it was the 'attitude' (what I often call the ethic inherent in revision; it is candor or the lack of it) that is the major hurdle in thinking.

'Although SE is often used when discussing religious belief, faith itself is not an exclusively supernatural belief, it is just a type of epistemology or method of reasoning that can lead to the building of unreliable knowledge or in fact no real knowledge at all'

In another article (Random Epistemologists) I attempted to explain and describe the reason why mistaking raw intuition as the basis for a complete method of building reliable knowledge is folly. Faith is usually awarded the vague description of 'hope or trust in things yet seen' with the obvious implication that whatever we want to be true is mysterious (IE fuzzy) and unseen but nevertheless just around the corner, inevitable. It's had plenty of revisions due to translation and interpretation (and this just within one of many similar traditions, just take your pick:

King James Version

Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

Darby Bible Translation

Now faith is the substantiating of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

World English Bible

Now faith is assurance of things hoped for, proof of things not seen.

Young's Literal Translation

And faith is of things hoped for a confidence, of matters not seen a conviction,

Enlightening? There certainly is one thing faith can provide and that is fairly much any rationalisation for holding onto a belief that seems to feel valid. Of course we can use far more poetic language. Since we can't see what it is we believe is 'yet to be or not seen', but because we've been told it's the epitome of love or terror and got the whole show going, we use an imagination which can analogise, often quite poorly. A favourite read of mine in my youth was the metaphysical poetry of John Donne. But let's face it, I was far more attracted to the images of young women it brought forth in my mind than any allusions to the supernatural. Donne's 'Knowing Faith' was far less appealing, mawkish and self eddifying. How can you know faith? Don't you mean pretend to know? Personally I loved much of the metaphysical poets because when done well it captured the reality of living - an emotionally torturous dilemma. The fact that we can have peace is only possible but for the reality of its opposite but this constant wailing for Utopias reduces it all to childish parable. My eldest daughter is playing her songs at the moment and I find it most compelling to just accept without judgement the emotionally captivating 'I fell into your arms..' I think it is far more enduring, real, to place one's emotions in reality, not fiction, no matter the cost.

King James Version

Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

Darby Bible Translation

Now faith is the substantiating of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

World English Bible

Now faith is assurance of things hoped for, proof of things not seen.

Young's Literal Translation

And faith is of things hoped for a confidence, of matters not seen a conviction,

Enlightening? There certainly is one thing faith can provide and that is fairly much any rationalisation for holding onto a belief that seems to feel valid. Of course we can use far more poetic language. Since we can't see what it is we believe is 'yet to be or not seen', but because we've been told it's the epitome of love or terror and got the whole show going, we use an imagination which can analogise, often quite poorly. A favourite read of mine in my youth was the metaphysical poetry of John Donne. But let's face it, I was far more attracted to the images of young women it brought forth in my mind than any allusions to the supernatural. Donne's 'Knowing Faith' was far less appealing, mawkish and self eddifying. How can you know faith? Don't you mean pretend to know? Personally I loved much of the metaphysical poets because when done well it captured the reality of living - an emotionally torturous dilemma. The fact that we can have peace is only possible but for the reality of its opposite but this constant wailing for Utopias reduces it all to childish parable. My eldest daughter is playing her songs at the moment and I find it most compelling to just accept without judgement the emotionally captivating 'I fell into your arms..' I think it is far more enduring, real, to place one's emotions in reality, not fiction, no matter the cost.

'Boghossian pointed out that it was the 'attitude' (what I often call the ethic inherent in revision; it is candor or the lack of it) that is the major hurdle in thinking'

So much of how we express what we believe or feel is true is nothing but philosophically circular rationalising. When we are desperate all we end up doing is arguing that something must be true because it is. And that's how we know it's true! We've all experienced this behaviour both for ourselves and with others. It is what we do when we are being belligerent and argumentative, childish and dogmatic. We can't even bare the idea of admitting, even hypothetically, that we might be wrong at all. Faith as an epistemology, as the principle, glorious, overarching method of constructing 'truth' is, upon examination, a naive, immature, arrogant and desperate attempt to avoid having to examine reality because, in the back of our minds, we understand that we cannot justify the claim other than to dig our heels in and scream. We can even do this:

"highly intellectualized poetry marked by bold and ingenious conceits, incongruous imagery, complexity and subtlety of thought, frequent use of paradox, and often by deliberate harshness or rigidity of expression."

We can merely suggest that what we believe, but cannot find, is hidden in the mystery among the metaphorical bushes. No you cannot. Good poetry expresses our emotional battles with reality. It should not be used simply to satisfy our childish need to never abandon the comfort of a mother 's breast.

In that other article I made the simple observation that the most devout will abandon faith thinking at the edge of each and every road because it can't help them know or be convinced of anything 'not yet seen' at all. And they damn well understand it at the time. But such is the depth of stupidity of the average human mind (and I do include myself) that we usually choose to embrace and maintain our own ignorance rather than risk the chance of learning something new.

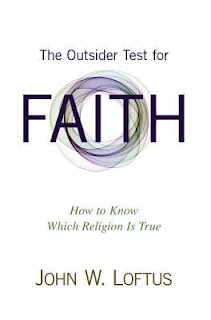

What harm is there, I once asked a friend and creationist, by just entertaining the hypothetical notion that there is no god at all of any description (there are so many), that it's all just a failed attempt at explaining? A mistake? What's not to learn? If a person chooses to examine their own religious belief John Loftus suggests the Outsider Test (no one is making you do it (as my mother would say)). If I believe in a Christian God, for example, do I think, hypothetically, I'd be just as confident in that belief if I'd be born in Tibet? The obvious answer is 'Of course not' but the strategy is not to attack a belief. It's to examine the methods we use to arrive at them. Why do we feel that simply playing with an idea (hypotheticals or thought experiments) is so frightfully dangerous? I want steak. No, no, I've changed my mind and back again. What's the problem? Religious traditions worked this out pretty quickly - in every such case the greatest sin, the most dangerous question of all, is to consider, even hypothetically, changing your mind. Wise and compassionate beings wouldn't care if we did such things, but humans with vested interests do. Even the average human will tend to regard their grown up child as having at least the right to their own opinion. I chose not to believe that god concepts describe anything real around 10 years ago, but the reason I did so was more important. No one, including myself, could construct a good reason for doing so. No one could possibly have such knowledge and critically, no one should leave such lousy thinking unexposed. Spreading the notion that faith thinking was virtuous was a dangerous folly. We cannot assess god concepts (or anything we can't even begin to locate) as we might approach the problem of teaching children how to cross roads safely. We wouldn't use faith or allegory. We would think it insane to say to little Johnny 'If you reach within you can know in your heart what is true'. If Johnny is subsequently squashed by a car we can then conclude that he just didn't have the type of faith that could move mountains (or stop cars or make himself fly, rise from the dead, etc). It may be confronting to think but given the circumstances (finite planet and an expanding human population) I rather feel it's important to at least discuss the prospect of a little more of it.

DS

Comments

Post a Comment